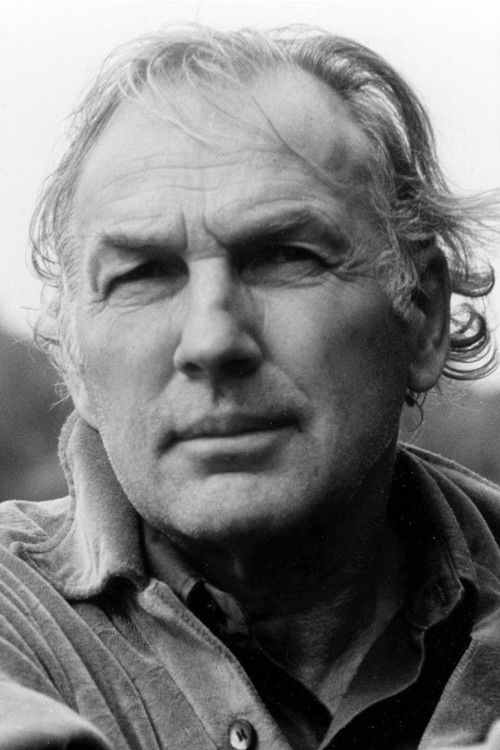

detail profile pierre perrault

Riwayat Hidup

Pierre Perrault OQ (29 June 1927 – 23 June 1999) was a Canadian documentary film director with the National Film Board of Canada.

Over his 40-year career, he directed 32 films and was one of Canada's most important filmmakers, although he was largely unknown outside of Québec.

Info Pribadi

Peran Yang Di Mainkan Pierre Perrault

Not far from the North Pole...

Not far from the North Pole...Icewarrior 1994

Not far from the North Pole on Ellesmere Island, for one hundred and twenty days, a watchful camera stalks a beast of fleece and hoof, the ancient musk-ox, in anticipation of the great bull's duel for dominance. By the light of late summer, in the hush of expectation of mating behaviour, battle is joined between the furry combatants.

A documentary film about a group...

A documentary film about a group...The Shimmering Beast 1982

A documentary film about a group of hunters who gather annually to hunt moose near Maniwaki, Quebec.

A look at November 15 1976 the date...

A look at November 15 1976 the date...15 Nov 1977

A look at November 15, 1976, the date the Parti Québécois seized power in the provincial elections, a victory that gave rise to an unprecedented outburst of joy at the Center Paul-Sauvé, a place where PQ sympathizers gathered.

Featurelength documentary on Hauris Lalancette a...

Featurelength documentary on Hauris Lalancette a...C'était un Québécois en Bretagne, Madame! 1977

Feature-length documentary on Hauris Lalancette, a Quebecer from Abitibi, who travels and draws surprising parallels between two corners of the country that are considered destitute and left behind. It is also about the search for ancestors and the nostalgia for old jobs that were better, both on the human level and on the technical level.

In the late 1960s with the...

In the late 1960s with the...Acadia Acadia?!? 1971

In the late 1960s, with the triumph of bilingualism and biculturalism, New Brunswick's Université de Moncton became the setting for the awakening of Acadian nationalism after centuries of defeatism and resignation. Although 40% of the province's population spoke French, they had been unable to make their voices heard. The movement started with students-sit-ins, demonstrations against Parliament, run-ins with the police - and soon spread to a majority of Acadians. The film captures the behind-the-scenes action and the students' determination to bring about change. An invaluable document of the rebirth of a people.

Essayfilm on a crucial issue the...

Essayfilm on a crucial issue the...Un pays sans bon sens! 1970

Essay-film on a crucial issue: the notion of belonging to a country. Lingered sentimentalism or deep psychological reality if one believes it is rooted in the heart of man? The action here takes place in the context of a nation that seeks: the French Canadians, and other people without a country: the Indians of Quebec, the Bretons of France. And here is the fundamental question posed: what are the "viable" peoples whose "maturity" allows them to "give" the autonomy and territory? And what is the environment that people can call "their country"?

The people of IleauxCoudres talk of...

The people of IleauxCoudres talk of...The River Schooners 1968

The people of Ile-aux-Coudres talk of their fading tradition of constructing boats to ride the seas.

From the lower St Lawrence a...

From the lower St Lawrence a...Beluga Days 1968

From the lower St. Lawrence, a picture of whale hunting that looks more like a round-up, with a corral, whale-boys and all. In 1534, when he stopped at the island he named l'Île-aux-Coudres, Jacques Cartier saw how the Indians captured the little white beluga whales by setting a fence of saplings into off-shore mud. In the film, the islanders show that the old method still works, thanks to the trusting 'sea-pigs,' the same old tide, and a little magic.

Four years after Pour la suite...

Four years after Pour la suite...The Times That Are 1967

Four years after Pour la suite du monde (1963), director Pierre Perrault asks Alexis Tremblay if he'll agree to travel with his wife Marie to the country of their ancestors, France. In a montage parallel, we follow them in France and listen to them talking to their friends about it.

At the instigation of the filmmakers...

At the instigation of the filmmakers...Of Whales, the Moon, and Men 1963

At the instigation of the filmmakers, the young men of the Ile-aux-Coudres in the middle of the St-Lawrence River try as a memorial to their ancestors to revive the fishing of the belugas interrupted in 1924.

The people of Unamenshipu La Romaine...

The people of Unamenshipu La Romaine...Attiuk 1963

The people of Unamenshipu (La Romaine), an Innu community in the Côte-Nord region of Quebec, are seen but not heard in this richly detailed documentary about the rituals surrounding an Innu caribou hunt. Released in 1960, it’s one of 13 titles in Au Pays de Neufve-France, a series of poetic documentary shorts about life along the St. Lawrence River. Off-camera narration, written by Pierre Perrault, frames the Innu participants through an ethnographic lens. Co-directed by René Bonnière and Perrault, a founding figure of Quebec’s direct cinema movement.

Did Cartier dream of making a...

Did Cartier dream of making a...The Land of Jacques Cartier 1963

Did Cartier dream of making a country from this land of a million birds? In his records of his exploration he certainly marvelled at seeing the great auks that have since disappeared from Isle aux Ouaiseaulx, the razor-bills and gannets that are gone from Blanc-Sablon, and the kittiwakes from Anticosti, all the winged creatures of all the islands which he described as being "as full of birds as a meadow is of grass". And that's not even counting the countless snow geese.

Four young men who belong to...

Four young men who belong to... After the death of her mother...

After the death of her mother... A business man plans to dump...

A business man plans to dump...