detail profile rachid boudjedra

Riwayat Hidup

Rachid Boudjedra (Arabic: رشيد بوجدرة) (b.

5 September 1941 in Aïn Beïda, Algeria) is an Algerian poet, novelist, playwright and critic.

Boudjedra wrote in French from 1965 to 1981, at which point he switched to writing in Arabic, often translating his own works back and forth between the two languages.

Boudjedra returned to writing in French in 1992 and has continued to write in that language ever since.

Educated in Constantine and in Tunis (at the Collège Sadiki), Boudjedra later fought for the FLN during the Algerian War of Independence.

He received his degree in philosophy from the Sorbonne, where he wrote a thesis on Céline.

Upon receiving his degree, he returned to Algeria to teach, but was sentenced to two years in prison for his criticisms of the government and was exiled to Blida.

He lived in France from 1969 till 1972, and then in Rabat, Morocco until 1975.

Boudjedra's fiction is written in a difficult, complex style, reminiscent of William Faulkner or Gabriel García Márquez in its intricacy.

La Répudiation (1969, "The Repudiation") brought him sudden attention, both for the strength with which he challenged traditional Muslim culture in Algeria and for the strong reaction against him.

Because a fatwa was issued which called for his death, he felt he had to live outside of Algeria.

He has routinely been called the greatest living North African writer.

Boudjedra was awarded the Prix du roman arabe in 2010 for Les Figuiers de Barbarie.

André Naffis-Sahely has translated two of his novels into English: Les Figuiers de Barbarie as The Barbary Figs (Haus, 2012) and Les Funérailles as The Funerals (Haus, 2015).

Rachid Boudjedra has also been involved in writing a number of films.

Chronique des années de braise (Chronicle of the Years of Fire), (dir.

by Mohamed Lakhdar-Hamina) which, in 1975 won the Palme d'or at the Cannes Festival.

Source: Article "Rachid Boudjedra" from Wikipedia in English, licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.

0.

Info Pribadi

Peran Yang Di Mainkan Rachid Boudjedra

By ending the life of Jean...

By ending the life of Jean...Jean Sénac, The Blacksmith of the Sun 2003

By ending the life of Jean Senac on August 30, 1973 in Algiers, his assassins believed they would silence him forever. They were wrong since his voice is a little louder every day. Witnesses to these craze: the publication of the complete works of this great poet, the countless conferences and radio broadcasts devoted to him and finally the production of films such as "Jean Sénac, the blacksmith of the sun". The moving and overwhelming testimonies of those who knew him, the unpublished film archives, the generous voice of the poet on the radio, the discovery of his travels in the territories of poetry and politics make this film a precious document on the life of Jean Senac.

After the battle of Kfar Chouba...

After the battle of Kfar Chouba...Nahla 1979

After the battle of Kfar Chouba in Lebanon in January 1975, Larbi Nasri, a young Algerian journalist, was caught in the whirlwind of events preceding the civil war. Linked to Maha, Hind, Raouf and Michel who surround Nahla, he witnesses the construction of the myth of Nahla, a singer adored by the Arab population. One day Nahla loses her voice on stage. The atmosphere of crisis that reigns around her is spreading like an infection. Larbi, fascinated, loses his footing and gets bogged down.

A meticulous chronicle of the evolution...

A meticulous chronicle of the evolution...Chronicle of the Year of Embers 1975

A meticulous chronicle of the evolution of the Algerian national movement from 1939 until the outbreak of the revolution on November 1, 1954, the film unequivocally demonstrates that the "Algerian War" is not an accident of history, but a slow process of suffering and warlike revolts, uninterrupted, from the start of colonization in 1830, until this "Red All Saints' Day" of November 1, 1954. At its center, Ahmed gradually awakens to political awareness against colonization, under the gaze of his son, a symbol of the new Algeria, and that of Miloud, half-mad haranguer, half-prophet, incarnation of Popular memory of the revolt, the liberation of Algeria and its people.

Le Doigt Dans LEngrenage is a...

Le Doigt Dans LEngrenage is a...A Finger in the Works 1974

Le Doigt Dans L'Engrenage is a film by Ahmed Rachedi, written by Rachid Boudjedra mixing fiction, filmed documents and interviews which recounts the arrival in Paris of an Algerian immigrant lost in the metro. On December 27, 1968, France and Algeria signed an agreement which admitted each year 35,000 Algerian workers to French territory in the France of the Trente Glorieuses where the annual growth rate reached 5% and where factories lacked workers. Candidates obtain a residence permit valid for 5 years for themselves and their families. Paris is committed to improving professional training and housing conditions for immigrants, too often confined to the most thankless jobs and often housed in slums. A testimony on the living conditions of emigrant workers "economic cannon fodder" of neocolonialism which simultaneously develops its alter ego, institutionalized racism, as a tool of social stagnation and division of the proletarian class.

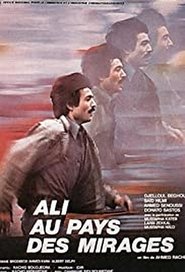

Ali an Algerian crane operator takes...

Ali an Algerian crane operator takes...