detail profile lawrence jordan

Lawrence Jordan

Lawrence C. Jordan

atau dikenal sebagai

Riwayat Hidup

Known principally as a maverick spirit in the world of avant-garde American cinema, Lawrence Jordan played an important role in the late 1950s and early 1960s San Francisco art scene.

Jordan has made over seventy experimental films, including a number of fanciful, filmic animations made from collaged cut outs of Victorian engravings.

The animations extend dreamlike imagery of collaged landscape into a cinematic realm of transformation and free form symbolism.

Jordan seeks to delve into the deep structures and Jungian connotations of the mythological images his films reference.

His alchemical approach to imagery creates what he has called the “theater of the mind, which you construct.

That is the Underworld.

.

.

the realm of the imagination.

You have to have a place to work with images.

”

Jordan founded the film department of the San Francisco Art institute in 1969 and taught there for over thirty years.

He made his own box assemblages in Cornell ’s lyrically evocative style since the mid-1960s.

Many feature ingenious mechanical and kinetic effects.

He continues to make films and box collages at his home and studio in Petaluma where he has lived since 1978.

Info Pribadi

Peran Yang Di Mainkan Lawrence Jordan

There is a hint of an...

There is a hint of an...Delirium 2018

There is a hint of an under water circus, and many of the performers are acrobats. The sea water, if that's what it is, is yellowish brown. A full-faced sun rises from the Sun King's cradle, while a moon of Saturn circles the planet. The cut-out animation moves airily through a time-distorted world, where dizziness barely maintains a balance, and conventional time-sense disappears. The music of John Davis, which has been slowed to half speed, reverberates eerily throughout the pulsing series of performances, and one wonders whether in the next scene one can catch one's balance. The timing throughout is musical, and suggests a barely upheld world of sanity; of course the dream world creeps into the conscious mind's puritanical sense of propriety, rendering a secondary sense of unbalance facing trial at the bar of...whatever comes to mind. Delirium?

This is a classing Jordan animation...

This is a classing Jordan animation...Night Light 2016

This is a classing Jordan animation, primarily in B/W, with touches of color. Actually, the engraved art work was film on color negative, so that subtle variations in tone are recorded. The mood--enhanced by John Davis' original music--is dream-like. It is both lyric and crackling, producing a kind of anticipatory tension. The scenes, in the usual Jordan manner, follow the surreal principle of placing objects and people where the ought not to be, and making movements that in the waking world are impossible. Each scene is a kind of drama from another world.

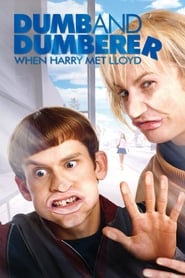

This wacky prequel to the 1994 blockbuster...

This wacky prequel to the 1994 blockbuster...Dumb and Dumberer: When Harry Met Lloyd 2003

This wacky prequel to the 1994 blockbuster goes back to the lame-brained Harry and Lloyd's days as classmates at a Rhode Island high school, where the unprincipled principal puts the pair in remedial courses as part of a scheme to fleece the school.

TAPESTRY part of Lawrence Jordans Odyssey...

TAPESTRY part of Lawrence Jordans Odyssey...Tapestry 1988

TAPESTRY, part of Lawrence Jordan's "Odyssey" triptych and filmed much later in Jordan's life, is a charged record of his bachelor life after marriage and child-rearing.

Ancestors is a film about spiritual...

Ancestors is a film about spiritual...Ancestors 1978

Ancestors is a film about spiritual forefathers and mothers in a purely fanciful sense. These are classical figures, anatomical figures, fairy tale figures and romantic figures all thrown in together - all my creative root-sources, in a kind of playful tribute. Like part 2 of Duo Concertantes, it's a moving single picture, now doubled.

Sepia toning lends a romantic even...

Sepia toning lends a romantic even...Visions of a City 1978

Sepia toning lends a romantic (even wistful) quality to Larry Jordan's film Visions of a City, which he shot in San Francisco in 1957 and edited in 1978. The pace is un-irritating, in contrast to the San Francisco of today; but unlike the equal weight Helen Levill gives to all her subjects, there is an internal evolutionary development in the Jordan film that ultimately delivers a story. Until the introduction of the human protagonist, poet Michael McClure, we are treated to an extravagant display of visual delights.

Animation The theme is Weightlessness Objects...

Animation The theme is Weightlessness Objects...Gymnopédies 1965

Animation. The theme is Weightlessness. Objects and characters are cut loose from habitual meanings, also from tensions and gravitational limitations. A lyric Eric Satie track accompanies the film. Such a portrait seems necessary from time to time to remind us that equilibrium and harmony are possible, and that we will not dissolve into a jelly if we allow ourselves to relax into them: A horseman rides through the landscape, through the town, but never arrives anywhere in particular. An acrobat swings on a rope above a canal in Venice, and is content just to swing there. Nothing threatens to disturb them. This film is a total contrast to the Kafka-like oddities of Eastern European animation. —Canyon Cinema

The Extraordinary Child applies his developing...

The Extraordinary Child applies his developing...The Extraordinary Child 1954

The Extraordinary Child applies his developing style to broad slapstick. His friends from the previous films and the director himself play out a riotous farce about an overgrown baby who steals his father’s cigars. Everyone mugs hilariously. The movie could be taken as another example of the Romantic notion of the artist as a monstrous child or misfit, or a parody of the same rather than the personal confessional statement seen so often in these film movements.

An anatomy of violence Four young...

An anatomy of violence Four young...Unglassed Windows Cast a Terrible Reflection 1953

An anatomy of violence. Four young men and two young women are on a drive. There's a rivalry between two guys for one of the girls. On a remote road, the car stalls. The driver hitchhikes for help. Led by the intrepid girl, the others walk toward abandoned buildings, perhaps a mining operation. One of the three guys sits and reads. The intrepid one explores the building and sees something that scares her. She screams; the two rivals and the second girl run to find her. Something she says starts a fight between her two suitors. The one reading a book walks away in disgust. After stopping the fight, the two young women follow. How can this end? Preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 2005.

This short piece is somewhat romantic...

This short piece is somewhat romantic... Orson Welles reads the poem especially...

Orson Welles reads the poem especially... Animation using cutout animation to craft...

Animation using cutout animation to craft...